In recent years, a tendency has arisen for historical linguists, e.g. scholars specialised in Indo-European historical and comparative linguistics, to join forces with scholars from related fields of research, including general linguistics, archaeology, historical philology, religion, history and natural history (e.g. historically oriented botany, geology and genetics). The Roots of Europe, having as its stated goal and as its raison d’être to examine and uncover Europe’s earliest languages, cultures and migration routes through interdisciplinary collaboration, is, I believe, a perfect model example of this recent tendency.

A randomly chosen example of what has become more elucidated thanks to the cooperation between Roots of Europe scholars is that a clear connection can be observed between linguistic factors and genetic migrations in Western Europe.

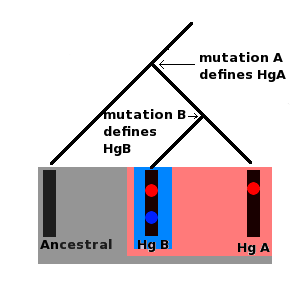

Historical genetics claims that human migration routes and history can be traced back to a sort of “genetic Adam and Eve” through the study of spontaneous changes – so-called mutations – in the DNA representing the male sex-determining chromosome (Y chromosome) and the so-called mitochondrial DNA. (mtDNA). Mitochondria are, in popularising terms, our cellular power plants: the energy needed by the cells is released in the mitochondria through respiration. Those two types of genetic material – the Y chromosome for men and the mtDNA for women – share as a common feature that they are inherited unchanged and in a direct line from father to son and from mother to daughter respectively… until a random mutation happens spontaneously only to be maintained and given forth in a straight line to the following generations on the paternal and the maternal side respectively.

That way, a typical Danish man or woman, for instance, is characterised by him or her carrying on an entire row or chain of Y-chromosomal and mtDNA mutations respectively that arose in earlier generations, whereas a newcomer from e.g. Africa will be characterised by a completely different mutation chain seeing that he or she has other ancestors in whom entirely different mutations have arisen. For the sake of convenience, a well-defined mutation chain is usually expressed in so-called haplogroups. Take for instance haplogroup R1b mentioned below: It covers the male Y chromosomal mutation of the chain “genetic Adam” -> M168 -> M89 -> M9 -> M45 -> M207 -> M173 -> M343 where each M followed by a number indicates a specific Y chromosomal mutation.

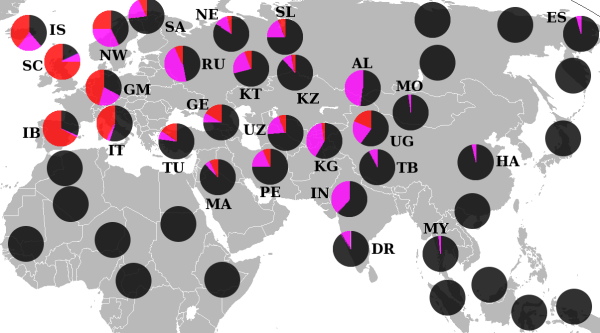

And now for what is relevant for this case: On the one hand, the geneticist Peter KA Jensen, one of Roots of Europe’s external researchers and collaborative partners, has informed the comparative and historical linguists employed at the centre about some of the results of the Genographic Project, viz. that Y chromosomal haplogroup R1b (see above) and the mutations characteristic for this group are particularly strongly presented in Western Europe, however strongest on the Iberian Peninsula.

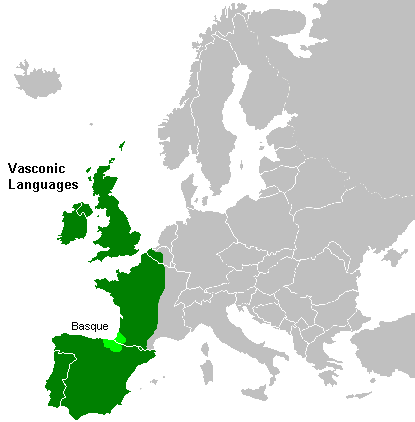

On the other hand, the Iberian Peninsula is also the centre of what can only be seen as a unique language. I am, of course, thinking of the Basque language that seems to have no known, close relatives, maybe apart from the now extinct Aquitanian language. Basque is, in other words, a linguistic isolate. All other languages of modern Europe fit nicely into either the Indo-European or the Finno-Ugric (Uralic) language family – but not Basque.

Now, the above considerations borne in mind, I find it extremely interesting that, according to another of Roots of Europe’s external researchers and close collaborators, the linguist Theo Vennemann, Basque(ish) elements can be found in a considerable number of languages of Northern and Western Europe – above all in the Germanic and the Romance languages. Most important and abundant are toponyms (e.g. river and mountain names) and metallurgical terms, but we also find many other words. Vennemann has, for instance, suggested that Latin grandis “large” has been borrowed from a pre- or proto-form of Basque handi “big”, and he has even managed to reconstruct phonological patterns for the loan word relationships between this pre- or ptoto-Basque language, named Vasconic, and the Northern and Western European languages. According to Vennemann, such circumstances are likely to indicate that the distribution of the Basque/Vasconic people has previously reached much further into the north-western part of Europe – at least compared to today’s situation with this once so widespread people having been forced back to a retreat in its core area: the Basque Country in the Pyrenees.

The distribution and prevalence of the above-mentioned haplogroup R1b, which the majority of scholars tends to associate with the Iberian Peninsula and the Basque people, goes perfectly well in hand with the alleged, former distribution and prevalence of the Basque/Vasconic language into the rest of northern and western Europe.

However, this case study has further perspectives: Through this very kind of collaboration, geneticists and linguists dealing with macro or long range comparison of languages and language families even further back in time might succeed in mapping the linguistic and genetic cohesion and migration routes of man all the way back to the exodus out of Africa.

The essence of this is, on the one hand, that all humans outside of Africa (and in a narrower sense even all from south of the Sahara) can unproblematically be traced genetically back to the mtDNA haplogroups M and N on the maternal side and to the Y chromosomal haplogroup CF, carrying the mutation M168, on the paternal side; and on the other hand that virtually all languages north of the Sahara may also be tentatively reconstructed back to a single language: Borean, including, inter alia, the Indo-European (e.g. Danish, Latin, Russian or Hindi), the Uralic (e.g. Finnish), the Sino-Tibetan (e.g. Chinese), the Eskimo-Aleut (e.g. Greenlandic/Kalaallisut), the Altaic (e.g. Turkish), the Afro-Asiatic (e.g. Arabic), the Dravidian (e.g. Tamil), and the Austronesian (e.g. Hawaiian or Indonesian) languages. In other words: Practically all language families outside of Sub-Saharan Africa. The linguistic part of this is, however, still highly controversial and uncertain, and only through future scholarship can it be shown whether this theory holds water.

Uncertain or not: What I believe to be the sticking point here is that we do find collaboration between comparative and historical linguists on the one hand and scholars from related fields, e.g. genetics, on the other hand.

—–

This blog post is based on the following article:

Hansen, Bjarne Simmelkjær Sandgaard (2009): “Sproghistorie i en større kontekst”. In: Sprogforum, vol. 47, pp. 49-51.

Joining forces is definitely fruitful – but at the same time very hard, methodologically. For instance, how can you _prove_ that the distribution of the R1b haplogroup and the Basque are connected phenomena? Just some points:

1) On linguistic side, Vennemann’s theory is very-very far from accepted. Thus, the proposed Vasconic area cannot be proved now (Especially because we know Iberian from Easstern Spain that is definitely not Vasconic).

2) On methodological side: R1b appears on Iceland, Scandinavia, Germany and Italy as well. Would you attribute this too to Basques?

3) Why Basques? You could also say, Celts. The distribution is fairly ok, actually better than in case of the Basque, especially because we know about Celts in Italy and Germany, for instance (+ some intermarriage with Scandinavians in Viking Age). So, how could you exclude this alternative scenario?