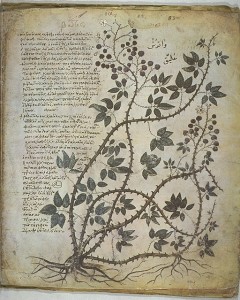

By definition, prehistoric practices are not described directly in any written sources. Indeed information might be gathered from the earliest attestations to the extent that they reflect an older state of affairs. In the ancient Iranian Vendidad, it is claimed that “divine words” are a better cure than knives or herbs, and numerous chapters are devoted to charms against evil spirits. Extensive catalogues are known from ancient India, notably the Sushruta Samhita (3rd or 4th c. AD), and from Greece and Rome such as the Hippocratic Corpus, Dioscorides’ De Materia Medica (77 AD) and Marcellus Empiricus’ De medicamentis (4thc.) with information on the popular use of plants for medico-magical treatment, some of which may continue much earlier traditions. However, in many cases ancient sources give no clear botanical meaning of a plant name, and even when the species can be defined, the status of the name may be unclear – we do not always know whether a given name represents a popular designation, a translation or simply an innovation by the author.

Archaeology can provide clues by human remains as may typological studies of aboriginal societies living under supposedly similar conditions, or even ethnobotanic studies of cultures believed to have retained ancient customs (such as the 3rd Danish Pamir Expedition 2010). However, since plants are subject to quick decay and spirits notoriously intangible, the archaeological evidence remains scarce and, as a result, conclusions suffer from a comparatively large degree of uncertainty (with the recent DNA-based identification of 15 plant species in ointments and herbal pills from a Greek shipwreck from 130 B.C. as one notable exception).

This is where etymology enters into the picture. As argued by J.D. Langslow (in Indo-European Perspectives, Oxford 2004), medical language is probably one of the most promising fields for semantic and etymological investigation. A way of linking information gained from archaeology and linguistics is the palaeolinguistic method: if the word for a certain creature, object or phenomenon is attested with regular sound correspondences in two or more languages, we must conclude that it existed in the homeland at the time before the dispersal of the protolanguage. Systematic studies of the European core vocabulary would have to include a stratification of the linguistic data, distinguishing between

1) substrata from indigenous non-Indo-European peoples

2) words of common Indo-European heritage

3) words belonging to a more restricted area

4) later cultural loans from known or unknown sources

From such an investigation, we would be able to draw conclusions as to which parts of the health domain, as it is known from the earliest attestations of Indo-European cultures, actually represent a Proto-Indo-European tradition, and which parts have arisen at a later stage, whether from creative innovation, contacts between the Indo-European branches or contacts with other language families. This may in turn tell us something more general about patterns of cultural evolution throughout history. Theoretically, it is not impossible that clues about forgotten types of plant medicine may be provided by new etymologies that will appear.

Searching for common anomalies often proves valuable. The almost identical Baltic words for two otherwise dissimilar plants ‘henbane’ (drignė) and ‘fool’s parsley’ (drignelė) make up a strong semantic parallel to those found in other Indo-European languages; thus, the Greek names for the two plants are apollon, apollinaris and aithousa respectively – Aithousa was the name of one of Apollon’s mistresses and meant ‘gleaming, burning’, and the traditional Latin name of the latter was exactly Apollon (borrowed from Greek). According to our cooperation partner Bernd Gliwa, these common names probably refer to dilation of the pupil of the human eye which is a well-known effect of both plants.

Celtic and Germanic languages share a lot of terminology from specifically this field (among them ‘fever’, ‘leprous’, ‘sorcery’, ‘demon’, several generic words for ‘illness’, medicinal herbs such as ‘Angelica’ and ‘holly’, and as many as 10 terms for ‘wound’ or ‘injury’). These items all look too old to be mutual loans, and since it can be showed by other means that Celtic and Germanic are not more closely related than each of them are with several of the other Indo-European branches, this indicates that at a certain point in their early history they shared a common vocabulary of both archaisms and innovations, reflecting post-Indo-European common beliefs in causes of illnesses and their treatments. Some of them may have been taken over from the same third source.

It is remarkable that, while the Germanic word *lubja- meant ‘strong plant-juice’ as well as ‘magic remedy; poison; magic’, its Celtic relative *lubī– meant simply ‘wort’. Finnish luppo means ‘lichen’ and is known to be an inherited word in the Uralic language family to which Finnish belongs. Lichen is used in traditional folk medicine as a laxative and against various kinds of pains, infections and inflammation. This points to a Uralic origin of the Germanic and Celtic words (there are no better candidates).

When dealing with plant-names one must be aware of the phenomenon of folk taxonomy whereby traditional ethnobotanical taxa may disagree with those of modern science (e.g. Lithuanian jonažolė ‘Hypericum’ but also ‘certain plants flowering at St. John’s, June 24th’). Our forefathers had other criteria for the classification of plants and animals. Sometimes these were given the same name because of a purely physical similarity, in other cases rather according to similarities in societal utility value or even mythological conceptions. Besides, some species have only a new scientific term and no separate folk name, either because they have lost it or because it was never relevant and the species was designated by a more generic term. Dialect material is extremely important because plant names and animal names often vary within small areas.

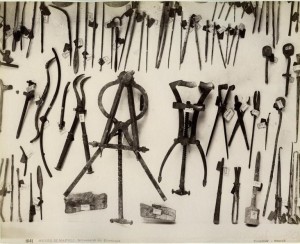

Relevant semantic fields may furthermore include words referring to symptoms; poison; nutrition and diet; fungi; salt, minerals and stones; exercise; hygiene and sanitation; body parts and bodily fluids; virginity, fertility and reproduction; maternal health, pregnancy and birth; puberty; congenital defects; body modifications; mood and sleep; mental disorders; ageing; cleansing of the dead; veterinary issues; folk legends; health deities; medical professions; and medical equipment.